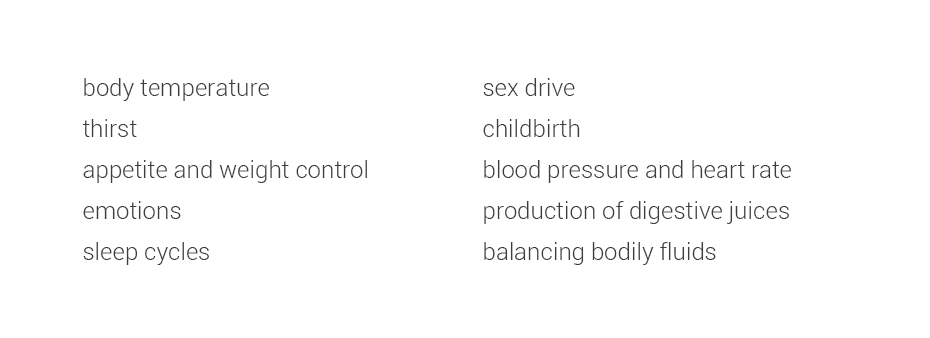

Resilience is defined as the ability to recover quickly from difficulties, toughness, or the ability of an object to spring back into shape; elasticity. As it pertains to the human body, resiliency is the ability to return to homeostasis following a stressor. While there are numerous physiologic mechanisms that provide resilience in our bodies, perhaps the most important is the hypothalamus. This relatively small area of the brain is responsible for most of the physiologic processes in the human body, including:

In most of these processes, the hypothalamus is responsible for restoring balance—in other words, the hypothalamus is responsible for resilience in our bodies.

But what happens when we lose resilience due to severe acute stress or prolonged and persistent stress? It appears two primary changes occur. The first is the loss of neurotransmitter function within the nuclei of the HPA axis, particularly the loss of glutamate and other neurotransmitters like dopamine, norepinephrine and even serotonin and GABA. The critical signaling that occurs within the nuclei of the HPA axis, such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the paraventricular nucleus, is diminished as the neurotransmitter levels decline and or receptor function is affected. The result is reduced capacity to organize a successful response to stress and is observed on salivary hormone testing as changes in the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR). The CAR is only measurable with three salivary cortisol samples collected at five minutes, 30 minutes and 60 minutes after awakening. These three cortisol measurements serve as a mini “stress test” for the brain and reliably tell if depleted HPA axis function has resulted in a loss of resiliency.

The second change that occurs when resiliency is lost is a disruption in circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are biological rhythms that exhibit three characteristics: 1) an endogenous free running (approximately) 24-hour period, 2) a rhythm that is entrainable, i.e., capable of phase reset by environmental cues and synchronization to the 24-hour day, and 3) exhibiting temperature compensation.

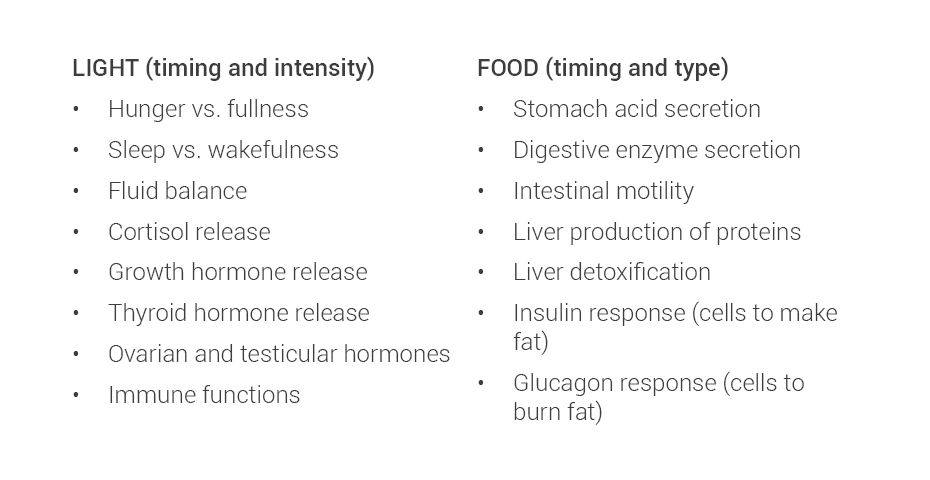

Food and light are the primary cues to entrain circadian rhythms. Below are the bodily functions each entrains:

When we, often unwittingly, deviate from ideal queuing of the circadian rhythms with aberrant patterns of food (eating from the first hour of waking to the last hour before bed) or light (not getting enough bright light during the day or two much blue light at night), then our ability to cope with stress is compromised. We have, in essence, lost resilience.

Circadian disruption can be picked up on the diurnal pattern of cortisol production on a six-point cortisol test as well.

In my next post, I will discuss symptoms associated with a loss of resiliency, including burn-out, and how to reestablish circadian functions to support the body’s response to stress and regain resilience in the HPA axis.

Christopher Mote, DO, DC, IFMCP

Christopher Mote, DO, DC, IFMCP earned his doctorate in osteopathy from the Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine at Midwestern University. He earned his doctorate in chiropractic and Bachelor of Science in human biology from the National University of Health Sciences (NUHS) in Lombard, Illinois, and is certified in Functional Diagnostic Medicine.

Dr. Mote also serves as the ARK Stress Recovery Program Clinical Expert at the Lifestyle Matrix Resource Center. With a focus on addressing the root cause of health concerns, Dr. Mote specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic health disorders.