As a clinician, you may be very familiar with patients walking into your office complaining of reflux-related symptoms. Alongside the discomfort these individuals experience (e.g., chest sensation, dysphagia, dyspepsia, and frequent coughing and clearing of the throat), they are often on medications like proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to help keep their symptoms at bay.

PPIs are among the most widely prescribed drugs worldwide and are seldom used judiciously for short-term treatment. Instead, patients are often placed on PPIs indefinitely without regard for the long-term consequences of these medications, and doctors indiscriminately refill their PPI prescriptions year after year. Unfortunately, this is an all-too-common scenario with concerning drawbacks for patients and clinicians alike.

PPIs and Nutrient Depletion

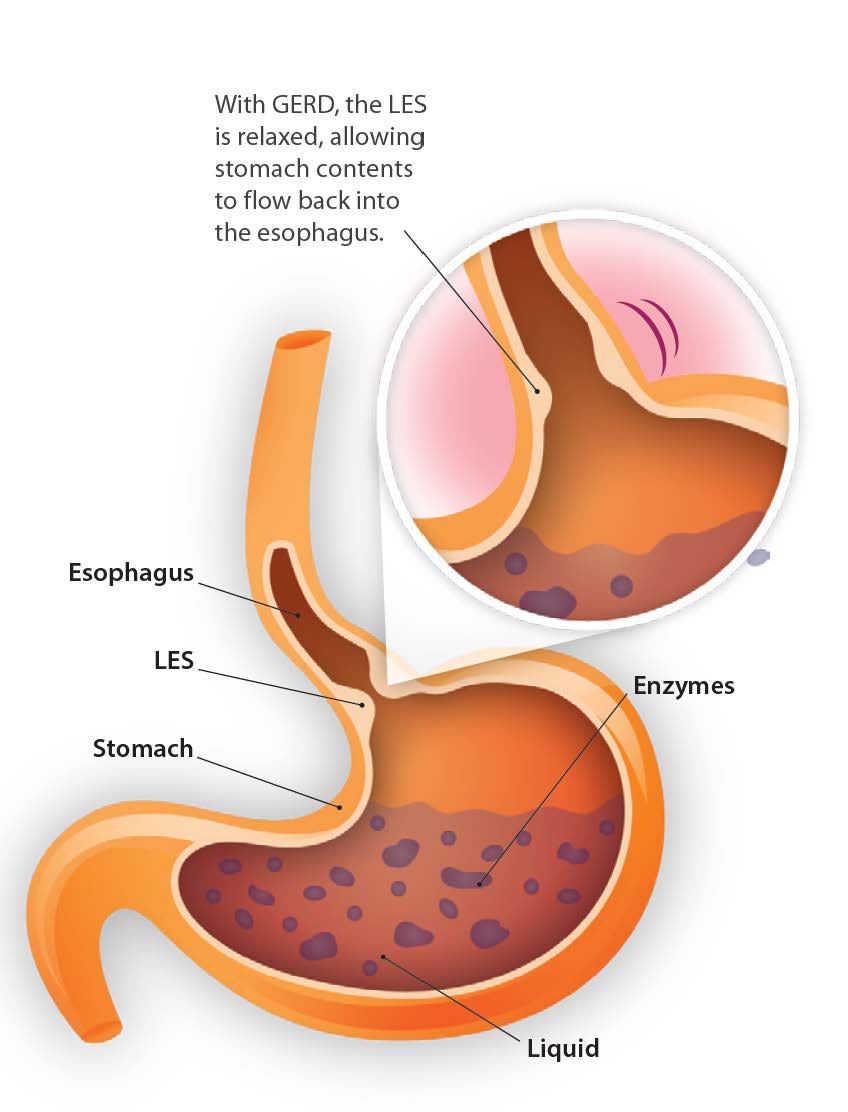

As the most common treatment for acid reflux-related symptoms, PPIs are medications that work to block enzymes to reduce the secretion of gastric acid in the stomach. However, through the lens of functional medicine, reflux caused by lower esophageal sphincter (LES) laxity occurs due to loss of function (too little acid production) rather than excess function (too much acid production). Ironically, this loss of function is the same reason used to justify over-prescribing PPIs among many doctors today. Low stomach acid production from chronic PPI use increases hypochlorhydria frequency around mealtime, which is commonly seen in older adults. As a result, these patients experience a variety of challenges from long-term use.1

Inability to Break Down Proteins

PPIs suppress pepsinogen’s conversion to pepsin, limiting the ability to break down proteins efficiently. The resulting amino acid deficiency puts patients at risk of malnutrition or even anxiety-type disorders from inadequate neurotransmitter production.

Low Vitamin B12 Absorption

B12 absorption requires gastric acid and involves pepsin in the stomach cleaving dietary B12 from proteins. This process enables intrinsic factor to bind to B12 so it can be absorbed into the blood from the small intestine.2 Vitamin B12 deficiency over long periods can result in memory issues, brain fog, and tingling and numbness in the extremities.

Decreased Vitamin C Synthesis

Vitamin C is secreted in human gastric juice, and PPIs affect vitamin C’s bioavailability by lowering acid concentration in gastric juices. Vitamin C deficiency symptomatology includes dry hair and nails, easy bruising, frequent nosebleeds, fatigue, and weakness.

Impaired Mineral Absorption

Minerals like calcium, magnesium, zinc and iron must be ionized with the help of acid in the stomach before being absorbed in the intestines.3,4 Mineral deficiency symptoms may include:

- Calcium: Muscle cramps, spasms, and increased risk of osteoporosis and bone fracture

- Magnesium: Paresthesia, headaches, cramps and constipation, as well as an increased risk of asthma and cardiovascular or gastrointestinal (GI) problems

- Zinc: Loss of appetite, unexplained weight loss and hair loss

- Iron: Anemia, mouth sores and ulcers

Microbiome Changes

Stomach acid makes it difficult for many organisms to thrive in the upper GI tract. A loss of acidity leads to a failure to suppress unwanted organisms and increases the risk of dysbiosis, yeast overgrowth (like Candida), C. difficile-associated diarrhea, or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).5

Challenges of Deprescribing PPIs

PPIs are one of the more difficult medications to deprescribe, testing the patience of the practitioner as well as the patient. PPIs are physiologically addictive to the mucosa, often resulting in severe rebound acidity during withdrawal, which is also known as rebound acid hypersecretion (RAHS).6

In addition, they are psychologically addictive to patients, who often cling to them for relief from very uncomfortable symptoms. The longer a patient takes PPIs, the harder it is to get them off the medication. With that in mind, restoring normal stomach function and reversing nutrient depletion after a person has been treated with PPIs for an extended period is often marked by successes despite some setbacks.

PPI Deprescription Support

Because compliance is paramount for getting patients off PPIs, it must be a gradual process guided by the practitioner, who also needs to provide patients with the confidence, education and clinical support they require. Gradually reducing or tapering treatment achieves greater success than abrupt cessation, and a gradual approach may allow for adaptation within the cells controlling HCl production.7

Supplementation to Manage PPI Withdrawal

In this journey, practitioners must incorporate nutritional supplementation to help manage symptoms and protect the stomach lining, including:

- L-glutamine to enhance the repair and regeneration of the cells in the mucosal lining

- Mucosa-supporting agents, like deglycyrrhizinated licorice, marshmallow root, slippery elm bark and aloe vera leaf gel extract, to provide an enhanced protective barrier over mucus membranes, soothe irritated tissues and restore normal inflammatory balance

- Herbal-based prokinetics, like artichoke and ginger, which can be used in combination to induce gastric emptying and help minimize the duration of heartburn-like symptoms

Replenishing Essential Nutrients

In addition, practitioners need to ensure their patients are getting their essential nutrients. While weaning patients off PPIs, one strategy for enhanced nutrient absorption includes taking the following supplements on alternate days when the patient

does not take their PPI.

- Multivitamins provide a full spectrum of vitamins and chelated minerals, including vitamin C, a B vitamin complex, calcium, magnesium, zinc and iron, to help replenish nutrients depleted by compromised absorption.

- Betaine HCL readily releases H+ ions to decrease pH, which acidifies the stomach, and pepsin initiates protein breakdown.

Final Thoughts

Prolonged use of PPIs poses a big problem for patients. They will need your help more than ever. Quitting PPIs cold turkey is not a viable option, and it may take several months to make progress with your patients on this front. In the meantime, targeted supplementation support will help make a positive impact on the associated symptoms and enhance the bioavailability and absorption of the vital nutrients they require for their overall well-being.

Joseph Ornelas, PhD, DC holds a PhD from University of Illinois with concentration in Health Economics, an MA degree in Public Policy from the Harris School at the University of Chicago, an MS degree in Health Systems Management from Rush University, and a DC degree from National University of Health Sciences. As a licensed provider and health economist, Dr. Ornelas has published numerous evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, helping to improve quality standards of care and provide value for health care practitioners across several specialty areas.

References

1. Heidelbaugh JJ. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4(3):125-133. doi:10.1177/2042098613482484.2. Busti, AJ. The Mechanism for Omeprazole Induced Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Risk of Developing Macrocytic Anemia, Hyperhomocysteinemia, and/or Neuropathy. Evidence-Based Medicine Consult. 2015.

3. Tran-Duy A, Connell NJ, Vanmolkot FH, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of iron deficiency: a population-based case-control study. J Intern Med. 2019;285(2):205-214. doi:10.1111/joim.12826.

4. Champagne ET. Low gastric hydrochloric acid secretion and mineral bioavailability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1989;249:173-84. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-9111-1_12. PMID: 2543192.

5. Freedberg DE, Lebwohl B, Abrams JA. The impact of proton pump inhibitors on the human gastrointestinal microbiome. Clin Lab Med. 2014 Dec;34(4):771-85.

6. Dacha S, Razvi M, Massaad J, Cai Q, Wehbi M. Hypergastrinemia. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015 Aug;3(3):201-8.

7. Haastrup P, Paulsen MS, Begtrup LM, et al. Strategies for discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014 Dec;31(6):625-30.

.png?sfvrsn=bea3ee8f_4)